10 free and low-cost ways to support the creatives in your community

Plus an exciting announcement about MY FIRST BOOK!

You’re reading Creativity Under Capitalism, a free biweekly newsletter about reclaiming and sustaining creative joy under tricky socioeconomic circumstances. I’m Adrianna, a journalist and creative writer based in Phoenix, AZ.

If you’re just getting settled in, check out previous issues of Creativity Under Capitalism—and if you like what you see, consider leaving a comment or buying me a coffee to make my day!

For now, I’m testing a new post cadence: Instead of receiving an issue every other Friday, you’ll get a new issue every other Wednesday. Thanks for your patience while I try this out! We’ll see if it sticks.

Also, this and future issues of Creativity Under Capitalism will be accompanied by an audio version, so you can listen on the go! Sorry in advance for when my cats inevitably meow in the background; otherwise, I hope you enjoy.

How do you support the writers, artists, and other makers in your life? And when you hear the word “support,” do you automatically think of the financial kind? If so, you’re not alone.

This summer, I asked Creativity Under Capitalism readers to share what they struggle with at the intersection of, well, creativity and capitalism. I received some very helpful insights (thank you for those!), among which was a comment from Jude Jones (they/them) about struggling to decide when to provide monetary support for another Substacker’s work. Paid subscription options abound—many of them $5 per month, some a little more—but that money quickly adds up when you’re supporting multiple writers, or, in Jude’s experience at the time, not pulling in any income.

This issue becomes even more complicated when you yourself are asking Substack users to support your newsletter with $5 or so each month; you can end up swapping the same Abe Lincoln around, which feels a little silly.

Jude’s comment made me wonder how we can support the creatives in our communities with little to no money, whether those people are family members, close friends, or strangers who live on the other side of town. It also got me thinking about how emerging, underground, and grassroots art economies often defy the economic models we’ve been taught are normal and trustworthy—and whether it’s a bad thing that they do.

All of us need money to live, and in an ideal world—Ireland, apparently—we’d have access to that money without having to strive for capitalism’s horrifically skewed definition of merit. Until we get there, most of us are stuck making money via some sort of labor and then spending that money on one of two things: stuff we need and stuff we want.

Often, art falls into the second category. (There are some forms of art, like food, that we need to live, but most of us will not die if we don’t buy a book, see a movie, or purchase a bespoke wool sweater.) Meanwhile, those who make art for a living—or are actively trying to make that their primary source of income—need to exchange their creative labor for money. This puts the creative in a tough spot: The creative needs their audience’s money, but their audience is under zero obligation to provide it.

To Jude’s point, it puts the audience member in a tough spot, too. Many of us want nothing more than to fling money at creative people in exchange for literature and cool photographs and tapestries and felted animal figures. Life is boring without those things. But we have to pick and choose.

On the creative’s side, there are strategies that might tip the audience member’s scales in one direction or another: offering increased “value” via behind-the-scenes looks, subscriber-only chats, and so on; emphasizing the handmade/small biz component by tucking handwritten thank you cards into orders or offering one-on-one attention; or connecting a body of work to a cause the audience really cares about, among others. If a person really likes you or your work, this might nudge them toward supporting you financially when they would have otherwise spent that money on, say, takeout or a new houseplant.

But what if that person doesn’t have room in their budget for non-necessities, and therefore can’t afford the takeout, the houseplant, or your work? What if, at the time they come across your work, they’ve exhausted their “want” budget for the week/month/year? Or what if you’re the one who wants desperately to support another creative, but doesn’t have any cash sitting around?

It’s time to turn to community support.

Even if a creative’s sole goal is to make money (which is rarely the case), they rely on forms of support that are not immediately financial in nature. People can’t buy a product they don’t know about, but in order to find out it exists, people need to talk about it. And in order to talk about something, one needs to build some form of relationship with that thing.

This is the essence of community (i.e. non-financial) support. Every time someone builds a relationship with a creative work, the potential for that work’s financial and cultural impact grows.

The good news is that, for the creative, helping one’s audience build a relationship with one’s work is often more fun than trying to convince them point-blank to hand over their money. Meanwhile, the audience gets to save their money—for now, at least; maybe that’ll change later, maybe not!—while knowing that they are still supporting an artist’s work. In the absence of abundant cash, this is a win-win.

In practice, community support looks like…

Sharing the article your local news organization wrote about the bakery that just opened down the street

Attending the video game launch party, author Q&A, or art gallery opening (or, if you can’t make it, sharing the flyer or social media post about it with folks who might be interested)

Sending an “I thought of you!” text to the friend who’d totally love that book or print or jewelry you just stumbled upon

Reading or listening to the interview an emerging artist did with an industry blog or podcast

Taking and sharing pictures at the art fair

Having more conversations about the art you find interesting or inspiring1

Requesting that your local library carry the book you want to read

Suggesting that book to your book club

Nominating your favorite works for awards, prizes, and other forms of recognition (or voting for them, if voting is open to the public)

Posting an enthusiastic review on Letterboxd, StoryGraph, Goodreads, Reddit, et cetera (and tagging that review appropriately—thanks Hanna Delaney for sharing that bit!)

Sending enthusiastic feedback2 to the artist directly

Engaging meaningfully in these ways escalates someone from audience member or customer to “creative citizen,” a term I began using after seeing Tin House co-founder Rob Spillman refer to himself as a “literary citizen.” Though it is a form of support, purchasing work from a creative person is transactional and often one-and-done, while making a habit of uplifting and discussing creative work establishes a longer-term and more robust relationship with that work and the community that surrounds it.

And creative citizenship is at the heart of many emerging, local, or DIY art scenes. When a creative person is surrounded by other creatives, it’s just not practical for them to make financial support their sole or primary response to other people’s works. Best case scenario, they’d all end up trading the same money around; worst case, they’d be broke all the time. Neither sounds very fun.

This is why I insist that my own readers (on Substack and elsewhere) not feel bad when they can’t offer support of the financial variety. Yes, I depend on my audience to buy my book—an exciting development we’ll get to shortly!—so I can show publishers how well-loved my work is and hopefully publish more books in the future. But people can’t buy my book if they don’t know it exists, and I only have so much reach, so I also depend on my audience to bring my book to their own communities. Whether they’ve already purchased a copy or can’t afford one at all, those who share my work with others are just as important to me as those who buy.

We live in such a money-centered world that it’s easy to forget how important non-financial forms of support are. Without those manifestations of enthusiasm or inspiration, however, the whole “community” leg of the creative lifestyle crumbles—and that’s why many of us create in the first place.

BIG NEWS!

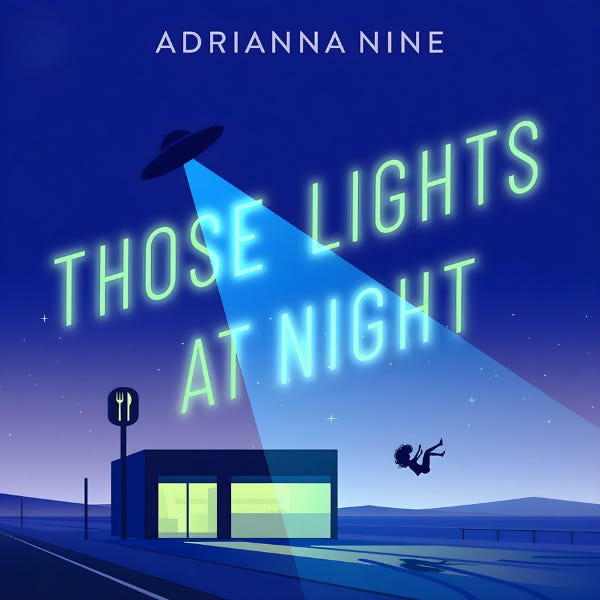

In lieu of a “what’s been inspiring me lately” section, I have a special announcement: my first book, Those Lights at Night, is available to pre-save on Spotify and pre-order via Barnes & Noble, Apple Books, Audible, and more! The audiobook officially comes out November 4. ❤︎

Produced by Spotify (under its brand-new Spotify Audio Selects imprint) and narrated by the wonderful Lindsey Dorcus, Those Lights at Night is a quirky, (mostly) lighthearted mystery built on sapphic pining, sarcastic dialogue, criticism of the growth-at-all-costs tech industry, and a very punchy setting.

Here’s the back-of-the-book blurb:

Bare Buttes is like any other California desert town: hot, dusty, and known best for its tourism. But unlike flashy Palm Springs or hipster Joshua Tree, Bare Buttes isn’t known for pool parties or hiking—its draw is its extraterrestrial visitors.

No one living outside the town needs to know that Bare Buttes’ “alien abductions” are fake, organized a few times each year by its small but spunky Performance Committee. The committee sustains just enough hype to avoid suspicion while keeping tourists interested, which is perfect for Juniper Flatts, the owner of a humble UFO-themed gift shop that she inherited from her mother. But when a series of real abductions occurs—each involving a mysterious flying vehicle not terribly unlike the Performance Committee’s simulations—and Juniper’s best friend and love interest goes missing, she takes it upon herself to find out who’s responsible for the chaos.

Juniper’s head-spinning investigation threatens to unravel the town’s carefully constructed image, and with it, the last thing Juniper’s late mother left her. By working with her neighbors to connect the dots, Juniper discovers the orchestrator behind her community’s biggest nightmare. Going head-to-head with him leads Juniper to a nauseating crossroads: sell out her community, or do the right thing, even at great personal cost.

Finally, if you live in or around Phoenix, I’m throwing a release party on November 4! I’d love to see you there.

If we’re being honest, this is one of the strategies—or dare I say habits—I find most important.

By “feedback,” I mean exclusively talking about the things you loved. Please don’t barge into someone’s inbox/comments section with constructive criticism, no matter how good your intentions are.

These are great ideas and loved the whole concept especially as someone without much disposable income at the moment.

Multiple people in my life set up booths at art fairs and local events. One way I've supported them is by providing company. At less busy events selling at booths is a lot of waiting and having someone else there can make all the difference.

One million percent YES to all of this!!!!