How to shift out of "work brain" and into creative mode

Adapting Emily Nagoski's emotional floor plan model for creativity—because moving toward art isn't terribly different from moving toward lust.

You’re reading Creativity Under Capitalism, a free biweekly newsletter about reclaiming and sustaining creative joy under tricky socioeconomic circumstances. I’m Adrianna, a journalist and creative writer based in Phoenix, AZ.

If you’re just getting settled in, check out previous issues of Creativity Under Capitalism—and if you like what you see, consider leaving a comment or buying me a coffee to make my day!

My professional life has changed a lot over the past six months. When I started this newsletter in 2023, I was a freelance writer working just 15-20 hours per week; today, I’m the editor of the site I spent the last four years freelancing for, as well as SFGATE’s part-time Southwest national parks editor—and I continue to freelance here and there. To say I spend a lot of my time and energy writing and revising for work would be an understatement.

But I still write Creativity Under Capitalism every other week, co-lead a weekly creative writing group, and work on a handful of personal writing projects. As proud as I am of my paid work, I don’t feel like myself when I haven’t written creatively for a while; journalism might satisfy the part of my brain that wants my words to fulfill a utilitarian purpose, but fiction and creative nonfiction satisfy my heart.

How can a person move between the two without ripping her hair out of her head? After a long day of editing technology news and drafting long-form pieces about the (soul-crushing) state of the national park system, how can a writer pivot from the rigid confines of practical journalism—or any other paid work, with all its restrictions and rules—to the colorful, boundless world of creative work?

It’s not a matter of simply hitting a switch, I’ve found. When my work began to change in March, I was beyond frustrated that when I shut my work laptop each evening and opened my personal laptop, I failed to enter the creative “zone.” The short story I’d begun writing in October sat untouched for two months, my brain unable to embody its characters or cadence; the novel I’d been stoked about plotting withered, unwatered.

I’m not embarrassed to admit that this resulted in a smattering of meltdowns. I woke up most mornings with a pit in my stomach, worried I had ruined my creative life by devoting more of my time to my professional one. I cried to friends over coffee, convinced that I would never be able to write for myself again. And I was angry. My world had lost its purpose, making all else appear ugly and gray.

After living this way—depressed, distraught, trying desperately to make headway on my creative work and failing—for a few months, I gave up. I accepted, angrily, that maybe my friends and my new therapist were right: In order to achieve one goal, I might have to set down another, at least for a while. In the evenings, instead of cracking open my personal laptop, I turned to baking, which I’d neglected. I started a new game of Ooblets.1 I read.

Not only did this make me a somewhat happier person (imagine that!), but my creative inklings slowly started trickling back. Ideas for Creativity Under Capitalism posts became abundant again. I started jotting down turns of phrase I thought would make good book titles. One night, I even bought a glass of wine at my favorite bookstore and worked on my short story for two hours without glancing at the clock until they were ready to close.

That’s great, Adrianna, you might be thinking, but when does the sex part come in?

Oh, right. That begins with this basic truth, which I learned by accident: Work and creativity rarely live next door to each other.

Let me explain.

Emily Nagoski, an incredibly clever and compassionate sex educator, published a book last year called Come Together: The Science (and Art) of Creating Lasting Sexual Connections, a sequel of sorts to Come As You Are for folks in long-term relationships. As a big fan of Come As You Are with plenty of sexual shame to spare, I snatched it up.

In the book, Nagoski describes something she’s dubbed the “emotional floor plan,” which illustrates how different people move through various mental or emotional states. The premise is that not all emotional states live next to each other, which means reaching a desirable state (in her case, lust) from a less-desirable one (stress, frustration, grief) often involves passing through a third, seemingly unrelated emotion; it’s often impossible to move directly between the undesirable and desired emotions.

Think about it: No matter where you stand inside your house, you’re probably unable to move to all of its rooms without passing through at least one other room along the way.

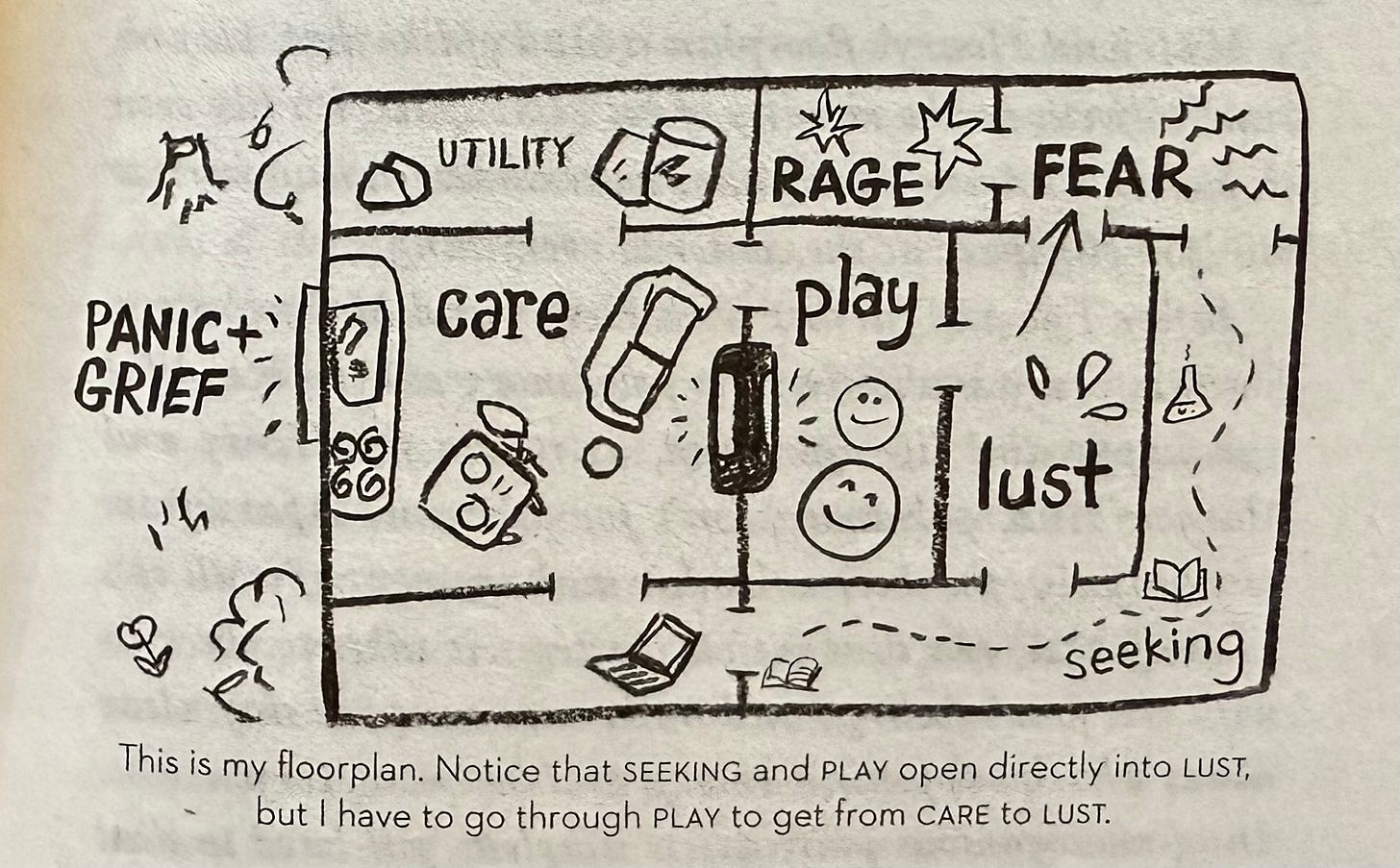

Per her own floor plan, Nagoski cannot move directly from a “utility” state (housework, errands, writing a book, and so on) to “lust.” Reaching lust first requires her to move through “care” (a mental or physical space focused on nourishment, ensuring one’s needs are met, and even love) and then “play” (laughing together, having fun for fun’s sake, or otherwise embracing lightheartedness). Only then does “lust” finally become accessible. Nagoski can also move from “seeking” (problem-solving, learning something new about a person, exploring novelty) to “lust,” but moving from a fearful, angry, or panicked state to a lustful state is a no-go.

Makes sense, right? If you’ve just experienced a trigger that reminds you of a past trauma, filed a claim with your health insurance provider for the umpteenth time, or put your kid down for a nap after listening to her scream for an hour, it’s probably going to take a few minutes (or more) for you to move into a sexy state of mind. You might want to turn on some fun music, make pancakes for dinner with your partner, enjoy a glass of wine, or go for a walk first—whatever suits your floor plan.

But while Nagoski’s model aims to demonstrate a personalized path toward lust, that’s not all it’s useful for. After all, each person’s floor plan also illustrates how their other mental or emotional states bump up against one another. One person might have an easy time moving from “anger” to “utility”; maybe righteous anger is what fuels their activism, or they find that doing something useful helps to smooth out their emotional tension. For another person, “seeking” and “play” might exist in the same open-concept room, allowing them to move between those states with ease.

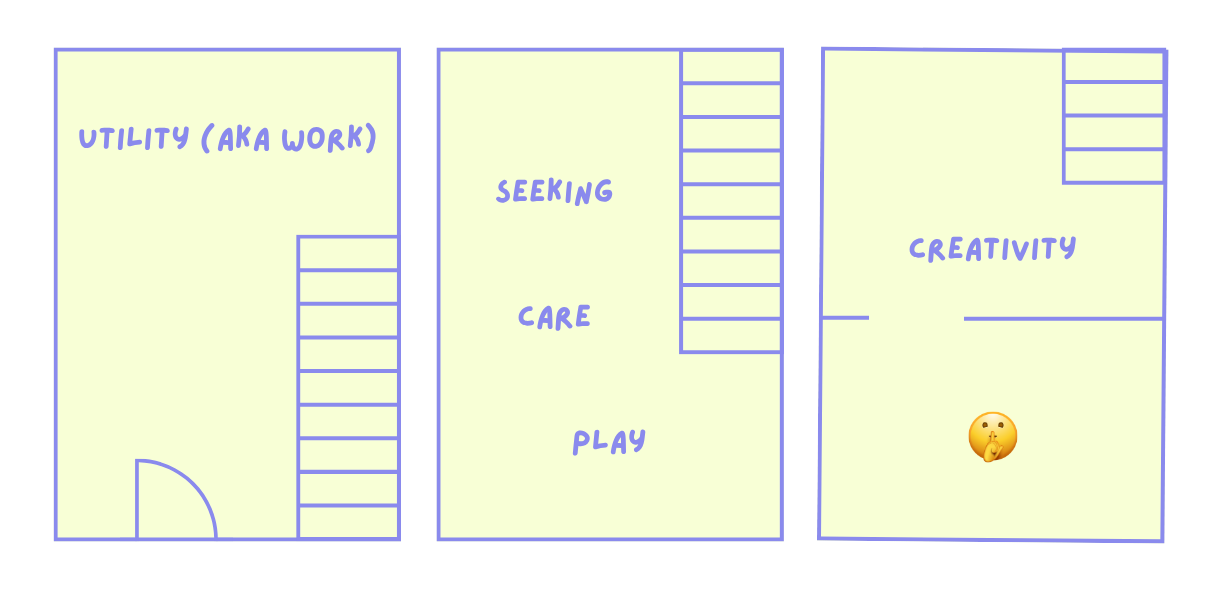

Nagoski’s model doesn’t include creativity as an emotional state, but I’ve found that the floorplan concept applies to creativity all the same. When I stopped forcing myself to transition directly from work mode to creative mode (something I never actually pulled off, hence my frustration), I inadvertently gave myself permission to pass through the rooms between utility and creativity. I was no longer asking myself to teleport from one state to another, which would have been impossible; instead, I moved from “utility” to “care,” “play,” and/or “seeking,” which (for me) are sandwiched between work and creativity.

It’s sort of funny, actually—I live in a three-story townhouse, and my office is on the first floor. My living room and kitchen are on the second floor, while my bedroom is on the third. I rarely do any creative writing in my office, since I spend so much time there for work; if I write for myself at home (instead of a coffee shop), it’s usually in the bedroom, where I lie on my stomach and attempt to defend my laptop’s keyboard from my cat.

This means that my emotional floorplan very closely matches my actual, physical floorplan: After I leave “utility” (floor #1), I need to spend a bit of time lounging on the couch, reading, cooking, baking, or playing a game (“care,” “seeking,” and “play” on floor #2) before moving up to “creativity” (or, sure, sometimes “lust,” but my mom and grandma allegedly read this so let’s quickly move on) on floor #3. “Seeking” and “play” activate my curiosity—an integral part of creativity, for me—while “care” ensures I have the energy to create in the first place.

Nagoski is a far more vibrant writer than I, and my explanation certainly pales in comparison with hers. (My example also skips the less-favorable emotional states, like panic and grief, for the sake of clarity and brevity.) But here’s the Tito’s six-times-distilled version of what I’m trying to say: It’s unfair to expect yourself to move directly from your “work brain” to your creative one. You probably need to pass through at least one other mental or emotional state along the way.

So, what does your emotional floor plan look like? What state of mind shakes off your business-casual attire—or your apron or lab coat or whatever else you wear for work—and sets you free to create? Is it a restful state, gained only after a luxurious nap? Or is it a seeking state that you find by jumping through a Wikipedia rabbit hole? Does a juicy, lustful evening jog your creative mind, or are you someone who can effectively turn rage into art?

I know that this is only half of the battle. This extra shift is an inconvenience; in a perfect world, none of us would have to work so much that simply transitioning into a creative mindset is both time-consuming and laborious. If you work overtime or have a child or battle mental illness or go to school part-time or have literally any responsibilities outside of a conventional work life, you probably feel that you don’t have time for this transition.

I’m with you there. The fact that art must come second to the work that puts a roof over my head pisses me off.

But the upside is this: Knowing what it takes for you to move between work and creativity makes that transition much more efficient. If you know that cooking with your partner or going for a run will allow you to step over the creative threshold, you can go do that, rather than wasting your evening wondering what the hell is wrong with you. The former is preferable to the latter, in my book.

What’s been inspiring me lately:

✰ The Art of Frugal Hedonism: A Guide to Spending Less While Enjoying Everything More2 by Annie Raser-Rowland and Adam Grubb. This brief read is less of a guidebook on how to save money (though there are some excellent practical tips in there) and more of a path toward rethinking your relationship with consumerism. I loved listening to the audiobook version; the Australian narrator is a hoot.

✰ Small Boat, Vincent Delecroix’s excellent novella inspired by the November 2021 English Channel migrant boat disaster. The book is narrated in first-person by the fictionalized woman responsible for the tragedy, and as a former first responder, I found this choice—and the prose itself—beautifully haunting.

If you play this game, please let me know. I haven’t met a single other person who does, but it’s one of my favorite video games of all time.

From now on, I’ll provide Bookshop affiliate links to the books I recommend through Creativity Under Capitalism. Purchasing via these links will not cost you anything extra, but a very small portion of Bookshop’s profit will support both the newsletter and Changing Hands, an indie bookstore and community organizing space in Phoenix, Arizona.

I love this! It explains why writing first thing in the morning works well for so many. During sleep the brain is often already in a semi-creative state through dreaming, so we start off closer to our end goal.

Your adaptation of Nagoski’s model for creativity is such a helpful reframing. I love how gently you remind us that creativity isn’t a switch to flip, but a space we enter with care, play, and patience.